Even though it is avoidable and curable, the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2015 estimated that 438,000 people died from malaria mainly in sub-Saharan Africa. John Lewandowski, a 26-year-old PhD student in mechanical engineering at MIT, said detecting it quickly is very important. “Early detection is very important, typically in the first five to seven days before symptoms arise so that treatment can begin,” said Lewandowski. He has made a mechanical device called RAM (Rapid Assessment of Malaria) that can diagnose malaria from a drop of blood in five seconds. There are two main ways to detect malaria: You can do a diagnostic test on a blood drop sample, which returns a positive or negative result, similar to a home pregnancy test or you can test a drop of blood under a microscope to find out the parasite.

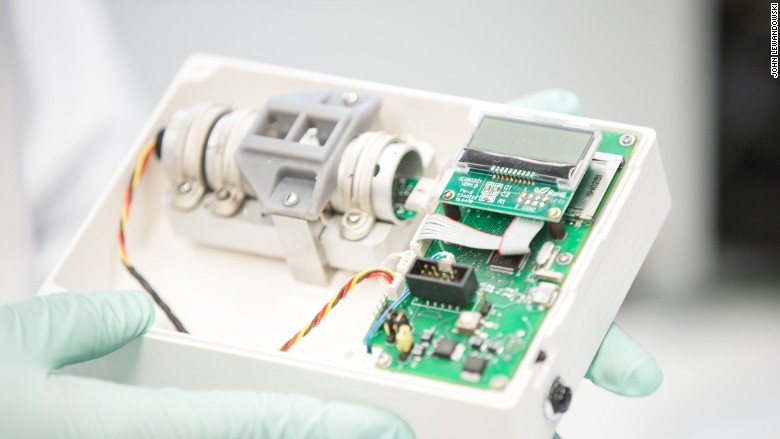

However, in Africa and Asia, many rural communities do not have the medical infrastructure for microscopic tests, and the diagnostic test cannot diagnose malaria infection in the very early stages. Lewandowski developed his device to make detecting malaria faster and cheaper. Costing about $100 to $120, the RAM is battery-operated and is made from low-cost materials. The plastic box (measuring 4×4 inches) has a small circuit board, a laser and a few magnets on the inside. It has an LCD screen, an SD card slot and a plastic disposable cuvette on the outside.

“It’s pretty bare bones,” said Lewandowski, who’s the founder and CEO of Boston-based Disease Diagnostic Group, which is manufacturing the device. Malaria parasites in human blood generate iron crystals that are magnetic in nature. “As an engineer, I thought about creating a way to detect these magnetic crystals quickly,” said Lewandowski. You take a finger prick of blood and put it into the box through the cuvette. If the malaria parasite is present, the magnets attract the iron crystals horizontally, vertically or diagonally. The laser helps recognize the pattern and detect the disease. (no crystals form, if the disease is absent). Even though detecting the parasite and finding out the treatment needs to be done by a local clinic or hospital, the technology is intentionally very basic and simple to use. “The technology is novel,” said David Sullivan, a professor at Johns Hopkins University and an expert on “hemozoin,” or the iron crystals. Sullivan, who is acquainted with the device, said it provides a small advantage over the quick diagnostic tests because of its speed; some malaria patients can die within 24 hours. Recently, quick blood testing devices have been in the public eye. Most obviously, Theranos, which stated that its blood testing device could process a full range of lab tests with just few drops of blood. The firm was valued at $9 billion, but in October 2015, a WSJ report raised queries over preciseness of Theranos’ blood tests and it has been under scrutiny since then. However, Lewandowski said his device isn’t reinventing the wheel. “Our technology is just speeding up that same process and bringing down the cost,” he said. Simultaneously, he said the company is trying to find out how the technology could pivot to test for other mosquito-borne diseases like dengue fever and Zika virus. The clinical trials of the RAM device have been tested by the Disease Diagnostic Group in India since 2013. “In India, the field study of 250 patients showed 93% to 97% accuracy,” Lewandowski also said that a new field study will be introduced this summer in Nigeria with up to 5,000 patients. The startup has won about $1.5 million from various business competitions, including the MIT $100K Pitch Competition and the Harvard Life Science Accelerator. “We self-funded initially and the rest of our investment is from prize money and grants,” said Lewandowski. He said the firm has six full-time employees and runs a lab and testing facility in Buffalo, New York. The doctors who are working in small clinics and individual healthcare workers and doing malaria field tests in India are already being sold the devices in limited quantities by the start-up. The firm has submitted the device for approval to the WHO and for EU health and safety certification. In a year’s time, Lewandowski anticipates to have RAM devices more extensively available for purchase, and ultimately in the hands of families in high-risk regions of the world for malaria. “For us, social impact is our mission,” he said. “We want them to be used in the right way by the right people who need them the most.”